Inviting your feedback on our climate information

We are running a short survey to understand how you use the climate information pages on our website. Your feedback will help us improve services and shape future products that better support your needs. Please use our Feedback Form to participate.

Below average rainfall across parts of New South Wales and southern Queensland

Rainfall was below average to very much below average (in the lowest 10% of all Novembers since 1900) for:

- parts of northern, central and eastern New South Wales

- areas in southern Queensland.

For New South Wales, area-averaged rainfall was 34% below the 1961–1990 November average, the lowest since 2020.

November rainfall was above average to very much above average (in the highest 10% of all Novembers since 1900) for:

- most of Tasmania and the Northern Territory

- large parts of Western Australia, Queensland and Victoria

- areas in northern and south-eastern South Australia

- north-eastern New South Wales.

Further details: Monthly climate summaries, Latest National climate summary

Spring rainfall – September to December

Spring rainfall was below average to very much below average (in the lowest 10% of all springs since 1900) for:

- much of southern and eastern New South Wales and northern Victoria

- parts of eastern South Australia

- areas in the south-west of Western Australia

- areas in southern and inland Queensland.

Rainfall for spring was above average to very much above average (in the highest 10% of all springs since 1900) for:

- most of Tasmania and the Northern Territory

- large parts of Western Australia

- northern and western Queensland, parts of south-eastern Queensland

- western South Australia

- some areas along the south-eastern coast.

For Tasmania, the area-averaged rainfall was 39% above the 1961–1990 spring average, the eighth-highest on record since 1900 and the highest since 1988.

Maps: Recent and historical rainfall maps

Drought recovery

In some parts of southern Australia that have experienced multi-season rainfall deficiencies, above average 2025 spring rainfall has improved root zone soil moisture, plant growth and some water storages. However, deeper soil moisture, groundwater, streamflow, ecosystems, and larger storages require sustained above average rainfall to recover from extended dry periods. Hydrological flow in some regions has not recovered from the millennium drought.

Climate change

State of the Climate 2024 indicated that there has been a shift towards drier conditions across southern Australia, especially for the cool season months from April to October. While some areas can have above average rainfall in some seasons, for southern Australia as a whole, April to October rainfall has been below the historical (1961–1990) average in 26 of the last 32 years between 1994 and 2025. The patterns of below average rainfall for southern Australia over the last three years reflect the climate change signal, over the last 30 years, reported in State of the Climate 2024.

The declining trend in rainfall is associated with a trend towards higher surface atmospheric pressure in the region and a shift in large-scale weather patterns. There have been more highs, fewer lows and a reduction in the number of rain-producing lows and cold fronts. Over the southern Australia region, there has been an increase in density, and therefore frequency, of high pressure systems across all seasons.

Long-range forecast for December to February

The long-range forecast, released on 4 December 2025 for December to February 2025 shows:

- Rainfall is likely to be below average for large areas of Australia and above average in parts of eastern and far northern Queensland.

- Daytime temperatures are likely to be above average across most of Australia.

- Overnight temperatures are likely to be above average across most of Australia.

Deficiencies for the 11 months since January 2025

For the 11-month, year-to-date, period since January 2025, areas with severe or serious rainfall deficiencies (rainfall totals in the lowest 5% or 10% of periods, respectively, since 1900) extend across small areas in:

- the Gascoyne and the central interior in Western Australia

- north-eastern agricultural regions in South Australia

- isolated parts of Victoria

- southern New South Wales

Since October, year-to-date rainfall deficiency areas have cleared in Tasmania, and almost cleared in Victoria. Deficiency areas have persisted in South Australia and Western Australia, and have expanded in southern New South Wales.

Deficiencies for the 22 months since February 2024

For the 22-month period since February 2024, which includes the last two southern cool seasons, areas with severe or serious rainfall deficiencies (rainfall totals in the lowest 5% or 10% of periods, respectively, since 1900) extend across:

- agricultural regions of South Australia

- much of Victoria, except parts of the north and east Gippsland

- parts of southern New South Wales

- some coastal margins in Tasmania.

Areas with lowest on record rainfall (compared to all respective periods since 1900) include:

- parts of Eyre and Yorke peninsulas, and from the Mid North district, east to the border, in South Australia

- small areas of southern and north-western Victoria.

Compared to October, lowest on record deficiency areas have contracted in southern Victoria, and have generally cleared in south-west Gippsland, and deficiency extent contracted in parts of northern Victoria. Deficiencies remained largely unchanged in South Australia, although there has been a reduction in the area of lowest on record rainfall.

Deficiencies for the 32 months since April 2023

For the 32-month period since April 2023, which includes the last three southern cool seasons, areas with severe or serious rainfall deficiencies (rainfall totals in the lowest 5% or 10% of periods, respectively, since 1900) extend across:

- areas in the west and south-west of Western Australia

- agricultural regions of South Australia

- areas of southern Victoria and isolated patches in the north

- a small area of alpine New South Wales

- some coastal margins, and a strip across eastern Tasmania.

Areas with lowest on record rainfall (compared to all periods since 1900) include:

- parts of the Yorke Peninsula and Mid North district in South Australia

- the coastline from Warrnambool towards Cape Otway in Victoria

- small areas near the south-west coast in Western Australia

Since October rainfall deficiency areas have slightly contracted in Victoria and Tasmania. Some South Australian deficiency areas have eased in severity and have cleared in parts of the far south-east.

.

Soil moisture below average in parts of the east

November root zone soil moisture (0–1 m) was below to very much below average (in the lowest 10% of Novembers since 1911) in:

- much of New South Wales extending into northern Victoria

- Queensland's south-west and South Australia's north-east

- Central areas of the Northern Territory

- parts of western and southern Western Australia.

Areas of soil moisture deficiencies expanded through parts of eastern Australia during November, with below average rainfall impacting New South Wales and south-west Queensland. However, higher than average rainfall eased deficiencies in south-east Queensland and parts of the south, including Victoria where very much below average conditions had been developing in the far-east.

Low soil moisture for long periods of time is an indicator of agricultural drought, affecting crop growth, and the pasture growth required for livestock.

Evaporative stress easing in parts of the east

Evaporative stress for the 4 weeks ending 30 November 2025 was elevated (negative Evaporative Stress Index (ESI)) in:

- much of New South Wales extending into northern Victoria

- Queensland's south-west and South Australia's north-east

- central areas of the Northern Territory

- parts of western and southern Western Australia.

During November, evaporative stress expanded and intensified in western New South Wales and bordering areas in South Australia and Queensland.

Evaporative stress eased in November in south-east Queensland into northern New South Wales, and across much of southern Australia including an area of far-east Victoria where evaporative stress had previously been significantly elevated (ESI below −2).

See this journal publication for further details on the calculation and use of the ESI in drought monitoring. Negative ESI values can indicate vegetation moisture stress reflecting agricultural and ecological drought. A rapid decrease in ESI values can be an indicator of flash drought.

Rainfall deficiencies and water storage at the end of November

- November rainfall was above average for most of Australia but below average for parts of New South Wales and southern Queensland.

- Year-to-date rainfall deficiency areas have cleared in Tasmania and significantly eased in Victoria and South Australia, but have expanded in southern New South Wales.

- Areas of long-term rainfall deficiencies have eased in intensity in parts of south-eastern South Australia and southern Victoria.

- Soil moisture deficits have expanded and intensified in central parts of the east and eased in parts of Victoria and south-east Queensland.

- Streamflow was below average at many sites across southern and eastern Australia.

- Some water storages in the eastern and southern states have declined by up to 50% compared to this time last year.

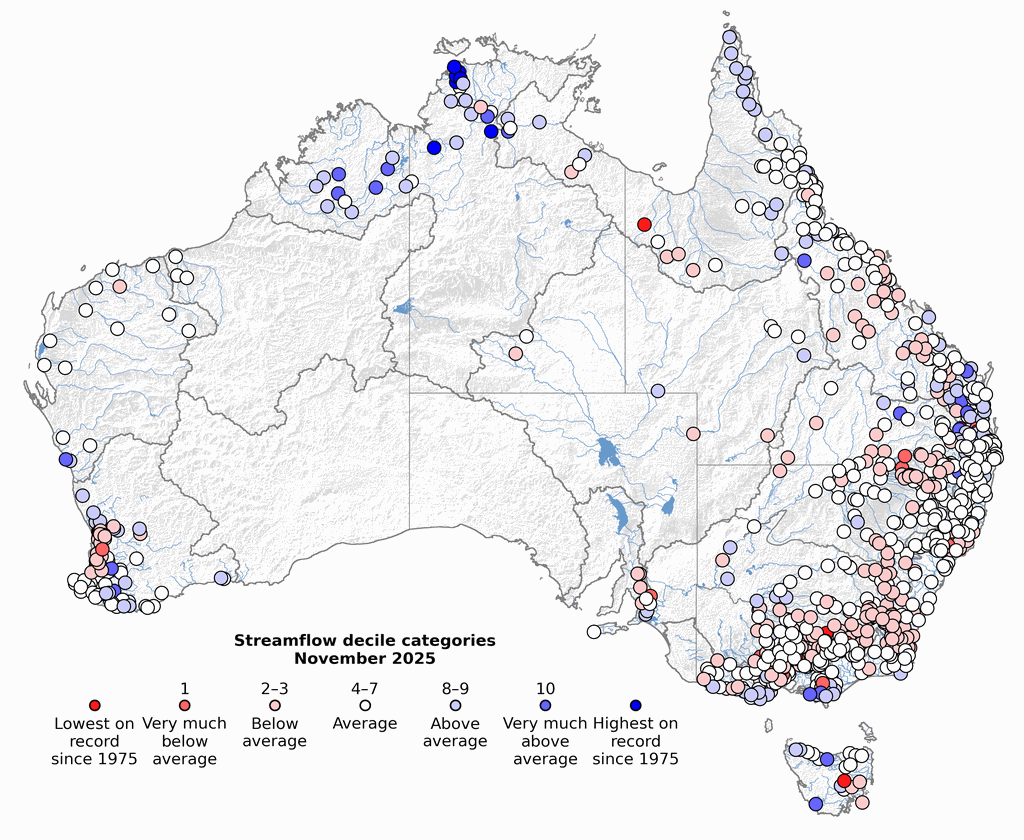

Low streamflow in southern and eastern Australia

Streamflow was lower than average at 30% of the 849 sites with available data across Australia in November (based on records since 1975). Many catchments in the south-eastern New South Wales and southern Queensland were getting drier than last month. These below-average flows were mostly associated with average to below average rainfall, which reduced root zone soil moisture and runoff across many catchments. Regions with a high proportion of sites with lower than average streamflow included:

- the South East Coast (Victoria) drainage division (15% of 86 sites)

- the South Australian Gulf drainage division (62% of 8 sites)

- eastern areas of Tasmania (23% of 18 sites)

- the Murray–Darling Basin (46% of 307 sites) and central and southern areas of South East Coast (New South Wales) drainage division (24% of 111 sites)

- the North East Coast (23% of 156 sites), five sites in the Carpentaria Coast and three sites in the Lake Eyre Basin drainage divisions in Queensland

- the central west of the South West Coast drainage division of Western Australia (27% of 77 sites), one site in the Pilbara–Gascoyne and one site in the Tanami–Timor Sea Coast drainage division.

Very much below average streamflow (in the lowest 10% of years since 1975) was recorded at 2% of sites in November, including:

- north-east and south-east areas of the Murray–Darling Basin

- a single site in the NSW, two sites in the central areas of the South East Coast (Victoria), a single site in the South Australian Gulf drainage division, and a single site in the Tasmania

- two sites in the south of the North East Coast drainage division and a single site in the Carpentaria Coast drainage division in Queensland

- four sites in the South West Coast drainage division of Western Australia.

Streamflow in November was average at 52% of the 849 sites with available data, across the country. Higher than average streamflow was recorded at 18% of sites, with 4% of sites observing very much above average streamflow (in the highest 10% of years since 1975). Regions with higher than average streamflow included:

- a the Tanami–Timor Sea Coast drainage division (79% of 28 sites), and eastern and western areas of the Carpentaria Coast drainage division (40% of 30 sites) and two sites in the Lake Eyre Basin

- the north and south of the North East Coast drainage division in Queensland (30% of 156 sites)

- the north of the South East Coast (New South Wales) drainage division (4% of 111 sites) and north-east and south of the Murray–Darling Basin (5% of 307 sites)

- southern coastal areas of the South East Coast (Victoria) drainage division (21% of 86 sites) and northern Tasmania (28% of 18 sites).

- the South West Coast drainage division of Western Australia (21% of 77 sites) and two sites in the Pilbara–Gascoyne drainage division.

Higher than average November rainfall increased runoff in northern Australia, parts of the west of Western Australia, southern coastal areas of Australia including Tasmania and south-east Queensland, contributing above average November streamflow in those catchments.

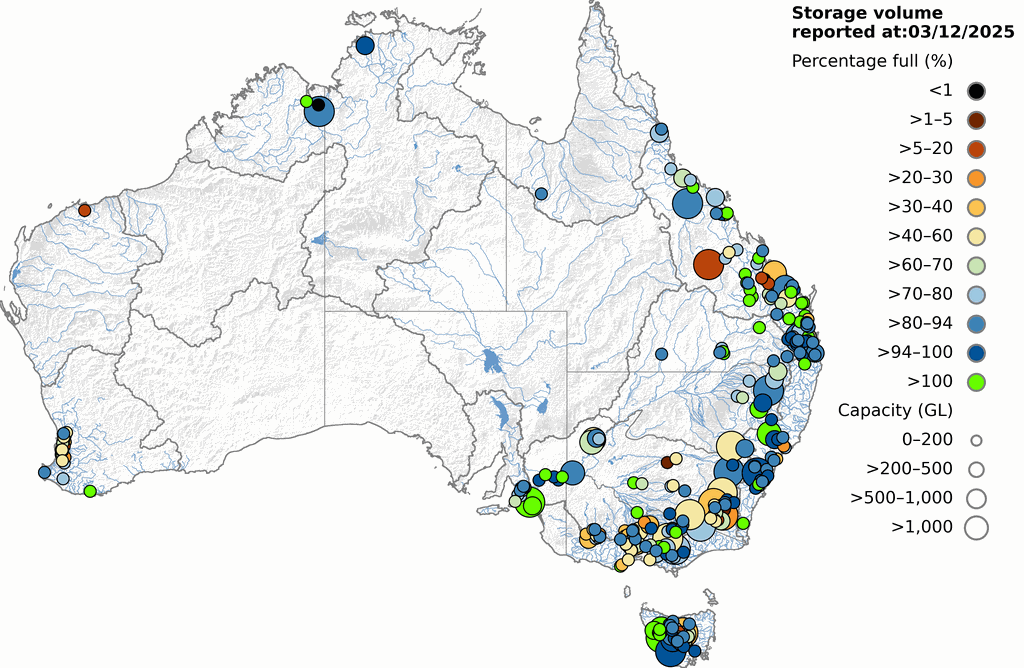

Low storage levels in western Victoria, the Murray–Darling Basin and central Queensland

By the end of November, total water storage across Australia—based on 303 public storages—remained steady at 69.3% of capacity, down by 0.1% from the previous month, but 2.3% lower than at the same time last year. Storage volumes decreased in 156 storages during November, with relatively low levels observed in several regions, including:

- the south-eastern Murray–Darling Basin

- Victoria, particularly in western areas

- central eastern Queensland

- the Harding storage in the Pilbara–Gascoyne drainage division

- Perth urban storages.

Declines in New South Wales and south-west Queensland were generally due to below average rainfall. Extremely dry conditions since winter 2023 in Victoria reduced inflows to the storages, and large volumes were diverted for agriculture during spring 2025. Extended dry spells over many years, despite occasional wet winters, have kept storages low in south-west Western Australia.

North East Coast

Storage volume decreased in 34 of the 69 storages in the North East Coast drainage division in Queensland during November. Overall, storages across the North East Coast drainage division were at 67.3% of capacity at the end of November, a monthly decrease of 1.3% and slightly higher, by 0.3%, than at the same time last year.

Several storages remained below 50% of capacity at the end of November, notably Fairbairn and Lake Awoonga, Queensland’s second- and fourth-largest storages respectively.

Fairbairn increased slightly by 0.3%, finishing the month at 16.9%. Despite this minor rise, overall volumes in the Nogoa-Mackenzie system declined to 17.3% of capacity in November. This system supplies water to rural communities across central Queensland. Lake Awoonga had a small decrease in November ending at 30.1%, 0.2% lower than at the start of the month.

South-eastern Australia

Many storages across the Murray–Darling Basin and the South East Coast (Victoria) drainage division were below or close to 50% of capacity by the end of November, including Hume Dam, Australia’s seventh-largest reservoir, and Lake Eucumbene. Hume Dam decreased by 5.4% during November, finishing at 43.7%, 11.3% lower than at the same time last year.

The overall storage volume across the Murray–Darling Basin decreased by 1.5% during November, finishing the month at 66.2% and 6.8% lower than at the same time last year. With dry catchment conditions and increased demand during the irrigation season (October to March), the storage volume decreased across southern Murray–Darling Basin.

Overall storage volume across the South East Coast (Victoria) drainage division increased by 1.2% in November, ending the month at 46.8%. In the Wimmera–Mallee system, a critical rural water supply for domestic and agricultural use in western Victoria, storages remained steady at 43.6% of capacity, down by 0.1% compared to the previous month. However, this is 7.9% lower than at the same time last year.

In Tasmania, the two largest storages—Lake Gordon and Great Lake—were at 61.3% and 39.2%, respectively, by the end of November. Total storage across Tasmania was 70.0%, an increase of 2.0% from October, and 5.6% higher than this time last year.

Western Australia

Harding Reservoir, the only major storage in the Pilbara–Gascoyne drainage division, was at 18.8% of capacity at the end of November, a decrease of 0.5% from the previous month, and 2.8% lower than at the same time last year.

Urban storages

At the end of November, surface water storages supplying most capital cities were above 75% of accessible capacity, with the exceptions of Adelaide, Perth and Melbourne. Storages for these cities remain relatively low, following extended periods of severe rainfall deficiencies reducing surface water inflows into regional storages.

Perth recorded slightly above average rainfall and soil moisture in November. Perth’s surface water storages were 45.8% full at the end of November, a decrease of 0.6% from the previous month, and 1.5% lower than at the same time last year. The two largest storages supplying Perth remained below 40% capacity, with South Dandalup at 10.1% and Serpentine at 33.4%.

The long-term decline in surface water inflows, driven by underlying climate change, means Perth now relies heavily on desalination and groundwater to meet urban water demand.

Adelaide’s storages were 67.2% full at the end of November, an increase of 1.4% from the previous month, and 18.0% higher than at the same time last year. Most of the storages in Adelaide remained above 60% capacity except South Para at 53.9% capacity. Storages rises were driven by operational factors, Murray River inflows and local catchment runoff.

Adelaide’s urban water supply is augmented by transfers from the River Murray, with additional support from desalination and groundwater. River Murray pipelines also supply water to the Eyre and Yorke Peninsulas and parts of south-east South Australia.

Melbourne's water storages declined sharply during 2025 due to a warm, dry autumn and winter with below average rainfall and streamflow. By the end of November, Melbourne's storages were 74.8% full, a decrease of 13.6% from the same time last year although an increase of 1.3% from the previous month.

In response to persistent rainfall deficiencies, the Victorian desalination plant has been in operation to support water supply to the Melbourne and Geelong areas.

Product code: IDCKGD0AR0

There are currently no formally monitored deficiency periods

During the absence of large-scale rainfall deficiencies over periods out to around two years' duration, the Drought Statement does not include any formally monitored deficiency periods. We will continue to monitor rainfall over the coming months for emerging deficiencies or any further developments.

Rainfall history

Australian rainfall history

Australian rainfall history

Quickly see previous wet and dry years in one (large) screen.

Previous three-monthly rainfall deciles map

See also: Rainfall maps | Rainfall update

Soil moisture details are reported when there are periods of significant rainfall deficits.

Soil moisture data is from the Bureau's Australian Water Resources Assessment Landscape (AWRA-L) model, developed through the Water Information Research and Development Alliance between the Bureau and CSIRO.

See also: Australian Water Outlook: Soil moisture

See also: Murray-Darling Basin Information Portal

Previous issues

Related links

![]() Unless otherwise noted, all maps, graphs and diagrams in this page are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

Unless otherwise noted, all maps, graphs and diagrams in this page are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence