Summary

A late-forming, weak La Niña formed in the tropical Pacific in September 2024, decaying in March 2025. The monthly relative-Niño3.4 index peaked in magnitude in January 2025 at a value of −1.36 °C.

Most atmospheric indicators were weak to moderate in strength during this La Niña, including trade winds and cloudiness. The monthly Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) values exceeded the La Niña threshold in 3 out of the 4 months between December 2024 and March 2025. The SOI is point-based and off-equatorial, representing the atmospheric pressure anomaly gradient between Darwin and Tahiti. The equatorial SOI, which represents the broader atmospheric pressure anomaly gradient between the equatorial eastern Pacific Ocean and the equatorial Indonesian region, was consistently typical of a La Niña.

The late event formation along with the influence of other factors (such as the record late start to the monsoon) likely resulted in atypical impacts (compared to La Niña patterns averaged over the historical record) to Australian rainfall. Overall, the weak La Niña did not appear to be the dominant influence, with its timing and strength suggesting that both short- and long-term climate drivers had a greater impact on rainfall outcomes.

Rainfall

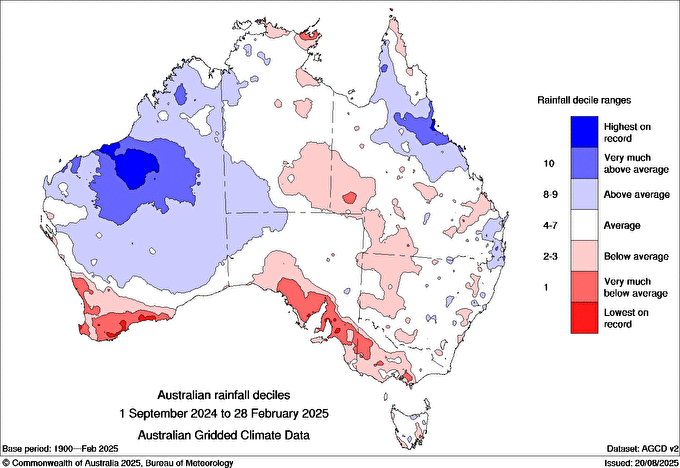

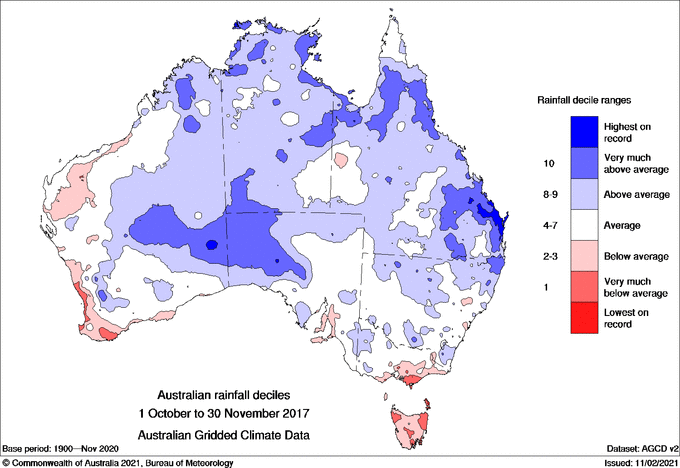

For the 6-month period September 2024 to February 2025, rainfall was above average for much of Western Australia and parts of northern Queensland (Figure 1). Rainfall was below average across much of southern Australia.

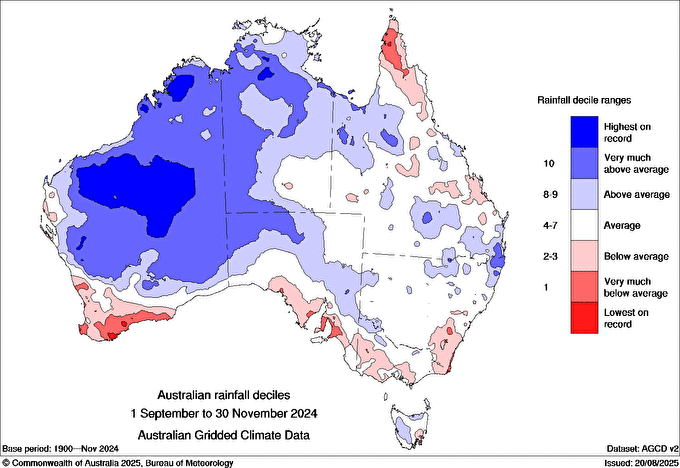

Spring 2024 rainfall was 36% above the Australian area-average, with western, central and northern Australia receiving above average rainfall (Figure 2). Only scattered areas of eastern Australia, including northern New South Wales and eastern and central Queensland received above average spring rainfall, with much of the eastern states close to average. Spring rainfall was below average across large parts of the southern mainland.

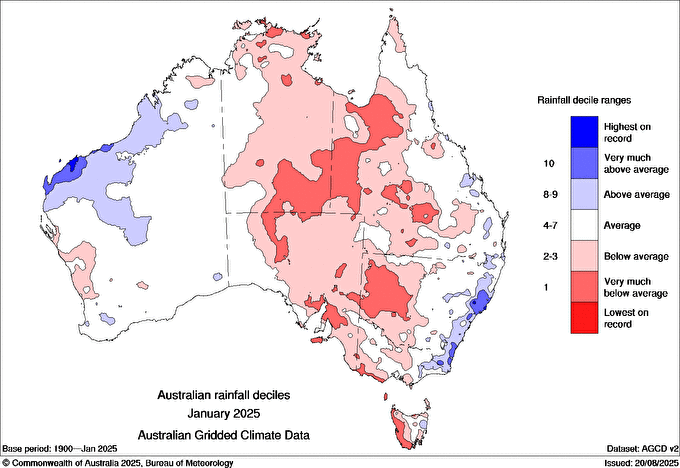

Summer rainfall was above average across parts of the east and north-west, while rainfall continued to be below average over much of southern Australia. Tropical influences such as the late arrival of the monsoon in Darwin dominated Australian rainfall patterns over summer, rather than the influence of a weak La Niña. While the peak magnitude of the relative-Niño3.4 index was observed in January 2025, rainfall was below average across much of northern Australia due to a lack of monsoonal activity (Figure 3).

While the relative Nino3.4 index was back in neutral territory by March, the month saw increased tropical low activity, with rainfall in the top 10% of records across much of north-eastern Australia.

Other impacts

There were 12 tropical cyclones during the 2024–25 tropical cyclone season; slightly above the long-term average of 10 per season, and higher than the recent average of 9 per season since 2000–01.

Historically, during La Niña events, maximum and minimum temperatures were typically cooler than average during summer across much of northern and eastern Australia. However, maximum and minimum temperatures in 2024–25 were warmer than average across most of Australia. It was the warmest spring on record and the second-warmest summer on record since national observations began in 1910.

More recently, while ENSO continues to play a part in year-to-year Australian temperature variability, global warming is the dominant influence on Australian temperatures.