There are currently no formally monitored deficiency periods

During the absence of large-scale rainfall deficiencies over periods out to around two years' duration, the Drought Statement does not include any formally monitored deficiency periods. We will continue to monitor rainfall over the coming months for emerging deficiencies or any further developments.

Rainfall history

Australian rainfall history

Australian rainfall history

Quickly see previous wet and dry years in one (large) screen.

Previous three-monthly rainfall deciles map

See also: Rainfall maps | Rainfall update

Soil moisture details are reported when there are periods of significant rainfall deficits.

Soil moisture data is from the Bureau's Australian Water Resources Assessment Landscape (AWRA-L) model, developed through the Water Information Research and Development Alliance between the Bureau and CSIRO.

See also: Australian Water Outlook: Soil moisture

See also: Murray-Darling Basin Information Portal

Previous issues

Related links

Rainfall deficiencies increase in the south-eastern quarter of Queensland

Rainfall deficiencies at shorter timescales such as the 11 months from April 2020 to February 2021 continue in parts of southwest to central Western Australia and the south-eastern quarter of Queensland.

Compared to the 10-month period ending January 2021, rainfall decifiencies have increased in both spatial extent and severity across the south-eastern quarter of Queensland.

In the west, above average rainfall for February 2021 resulted in a substantial lessening of deficiencies across much of Western Australia, although serious or severe rainfall deficiencies persist in some areas.

Rainfall in the past month has contributed further to gradual recovery from longer term multi-year rainfall deficits in parts of the west, while in Queensland multi-year rainfall deficiencies have generally increased. Deficiencies for the periods January 2017 to present and January 2018 to present still exist over very large parts of the country. More rainfall is needed over an extended period to fully recover from the extended dry conditions of 2017 to 2019.

The Climate Outlook, issued 4 March, indicates rainfall during March to May is likely to be above average across most of Western Australia, South Australia, southern Queensland, New South Wales, northern Victoria, and eastern Tasmania.

11-month rainfall deficiencies

Serious or severe rainfall deficiencies for the 11-month period April 2020 to February 2021 are in place in Western Australia in north-eastern parts of the South West Land Division, the south-eastern Gascoyne, and adjacent parts of the Goldfields District. Deficiencies have lessened substantially compared to the previous 10-month period following above average February rainfall.

In eastern Australia, a drier than average month for much of Queensland resulted in an increase in rainfall deficiencies. Deficiencies extend across an area of the south-eastern quarter of Queensland covering the Capricornia, Wide Bay and Burnett, and Central Highlands and Coalfields districts, and the south-east apart from the coastal strip.

Extended dry conditions over eastern Australia

Australia has experienced a prolonged period of below average rainfall spanning several years.

Rainfall deficiencies have affected much of Australia since January 2017. Multi-year rainfall deficiencies and their impact on the Murray–Darling Basin are discussed in Special Climate Statement 70 and the dry conditions over Eastern Australia for the period commencing January 2018 are described in Special Climate Statement 66. The strip along the west coast and south coast of Western Australia has also been affected by rainfall deficiencies for the periods commencing January 2017 and January 2018.

For periods longer than 24 months, the greatest impact of the prolonged below average rainfall has been in the cooler months of April to October. Large parts of the country remain in severe rainfall deficiency for the 35-month period from April 2018, though rainfall last year and in early 2021 has seen improvement across many areas. Above-average February rainfall has eased longer-term deficiencies in the inland west of Western Australia, while in Queensland the severity of multi-year rainfall deficiencies has generally increased. Elsewhere multi-year rainfall deficiencies are largely unchanged.

Persistent, widespread, above average rainfall is needed to lift areas out of deficiency at annual and longer timescales and provide relief from the impacts of this long period of low rainfall (such as renewing water storages). The impact of the longer dry on water resources is still evident, especially in northern parts of the Murray–Darling Basin where total storage levels remain low.

The role of climate change in rainfall reduction over southern Australia and along the Great Dividing Range is discussed in State of the Climate 2020. Parts of southwest, southeast, and eastern Australia—including parts of southeast Queensland and southern and eastern New South Wales—have seen substantial declines in cool-season rainfall in recent decades.

Soil moisture

Compared to last month, root-zone soil moisture (in the top 100 cm) has decreased across much of Queensland and north-east New South Wales, and increased across much of Western Australia and parts of south-east Australia.

Soil moisture was below average for part of eastern Queensland extending from around Mackay into the Wide Bay and Burnett region, and inland into the Central Highlands. Soils were wetter than average for the month across much of Western Australia, the south-west Northern Territory and the Top End, parts of the Cape York Peninsula, most New South Wales and Victoria, parts of southern and western South Autralia, and much of Tasmania.

The influence of very low rainfall over longer timescales is still evident in the 17-month soil moisture for October 2019 to February 2021, which was very much below average over large areas, predominantly in the southern half of Western Australia, but also in parts of Queensland extending from the east coast through central and northern Queensland to the Northern Territory border.

- Deficiencies continue in the south-eastern quarter of Queensland, and have increased in severity compared to last month

- Deficiencies also persist in parts of south-western to central regions of Western Australia, but the size of these areas has decreased substantially following above average February rainfall

- Accumulated rainfall deficits at multi-year timescales remain significant in many parts of Australia, and may persist for some time

- Root-zone soil moisture has decreased across much of Queensland, and increased across much of Western Australia and parts of south-east Australia

- Major water storage levels remain low in the northern Murray–Darling Basin

- Northern Australian water storages increased significantly in response to the northern monsoon

- South East Queensland storages remain low

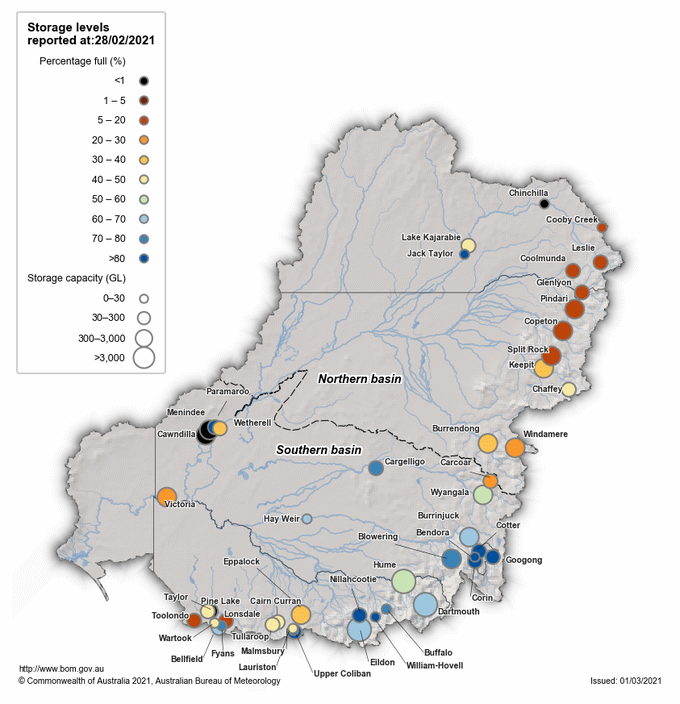

Major water storage levels remain low in the northern Murray–Darling Basin

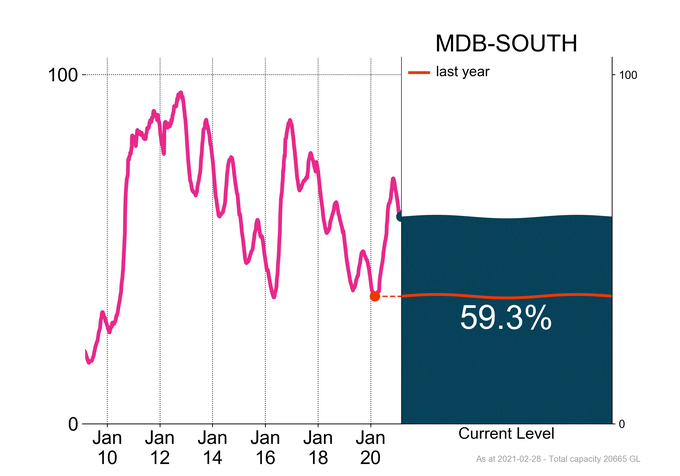

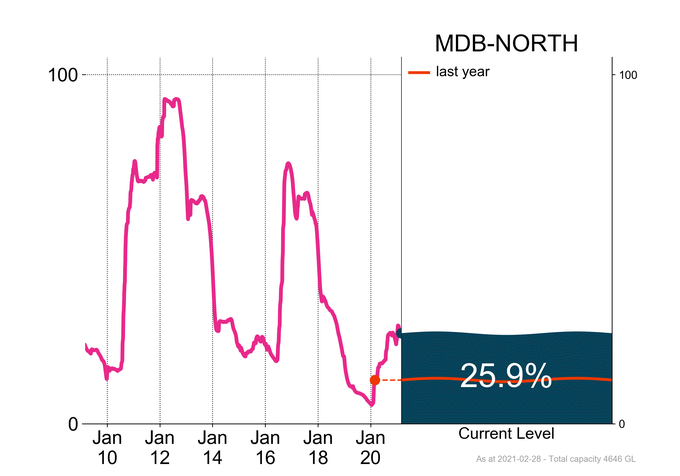

The total water storage in the Murray–Darling Basin decreased slightly in February but remains in a significantly better position than at the same time last year. Total storage was 53.2% of capacity at the end of the month, a decrease of 0.9% of capacity since last month, but much more than for the same time last year when it was only 32.1%.

Total water storage in the northern Basin decreased by 1.5% to 25.9% of capacity (1,272 GL) at the end of February, but is still 13.4% higher than the same time last year. Despite average rainfall occurring in much of the northern Basin in February, most of the storages decreased slightly. No storage was at greater than half of capacity, except Jack Taylor (90.4%) in the north.

Despite above average rainfall across the catchments where major storages are located in the southern Basin, the total storage decreased slightly to reach 59.3% (12,258 GL) of capacity; still significantly higher than February 2020 when it was only 37.4%. Storages often decrease in summer as this is typically a draw-down period in the southern Basin.

Further detail on individual Murray–Darling Basin catchments can be found in the fortnightly Water Reporting Summaries for MDB Catchments.

Northern Australian water storage levels have increased significantly

The northern Australian monsoon season commenced in December and since then above average rainfall has occurred. In response, the volume of water in two of the major water storages in northern Australia has increased significantly. Water levels in Lake Argyle, the largest water supply storage in Australia (10,400 GL) had been decreasing since September 2017 as the past three wet seasons had not delivered significant inflows to the storage. This year's monsoon started to bring relief and the gradual wet season filling escalated in February to increase Lake Argyle's storage volume by 24.1% to reach 55.5% of accessible capacity. In a similar way, the Darwin River storage increased by 21.1% in February to reach 80.1% of its capacity.

South East Queensland storages remain low

Despite good rainfall across most of the continent, the south-eastern part of Queensland received below average rainfall in February. The volume of water in the largest storage in the area, Wivenhoe, continued to decrease in February, following the trend of the last three years, to reach to 36.5% of capacity at the end of the month.

Product code: IDCKGD0AR0

![]() Unless otherwise noted, all maps, graphs and diagrams in this page are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

Unless otherwise noted, all maps, graphs and diagrams in this page are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence